Meet with Emilie Dotte-Sarout who recently joined the University of Western Australia as an ARC DECRA Research Fellow to work on her project “Pacific Matildas: Finding the Women in the History of Pacific archaeology”.

Tell us about the history of women archaeologists in the Pacific and the struggle against oblivion in an environment that was mostly designed for male scientists.

I am focusing on the history of the first women who worked as archaeologists in the Pacific region, and those who most actively contributed to developing this field of scientific studies, especially between the end of the 19th century and the mid-20th century. At that time, women in general had a hard time getting access to scientific training, and struggled to obtain diplomas. Even if these women were sometimes allowed to attend university, they were not always allowed to sit for the exams nor practise their profession and work as scientists, and this standard lasted in many European countries until the turn of the 20th century. These difficulties meant it was mainly women from relatively wealthy and open-minded families who managed to access the discipline – often as volunteers, assistants or professionally-trained amateurs.

Even those women who succeeded in practising as archaeologists, who left valuable work behind, and had their skills acknowledged by their contemporary male peers, continued to face gender-based discriminations. As a result, the legacy of their research has faded away very quickly compared to male scientists. As one first-hand example: when I was a student of Pacific archaeology in the 2000s, we heard a lot about the “founding fathers”, such as Roger Green, Edward Gifford, José Granger, Richard Shutler, Kenneth Emory, Ralph Linton (first PhD in Pacific archaeology in the 1920s)…

We learned a lot less about Mary-Elisabeth Shutler who played a critical role in the first professional expedition of archaeology to New Caledonia in the 1950s. Few scholars would be familiar with the work of Aurora Natua from Tahiti, despite the fact that she coordinated fieldwork access for archaeological research conducted in French Polynesia between the 1950s and the 1980s – including some of those led by J. Granger, R. Green and K. Emory. It is also worth noting that the second ever PhD in Pacific archaeology was obtained by a woman – Laura Thompson – in the early 1930s.

We tend to forget that many female researchers contributed to the groundwork alongside these famous male figures, and that many wives took part in archaeological excavations, data analysis and monograph writing, sometimes only to have their contributions moved to the acknowledgement section rather than recognised as co-authors. (Douglas and Carolyn Osborne in the mid-20th century).

The story of Adèle Dombasle, a female explorer, scientist, and talented illustrator of the 19th century (and incidentally the ancestor of a famous French actress) is extremely inspiring. It is a story of discrimination, but also of resilience and, ultimately and in a biased way, accession to a form of public recognition.

Adèle (Adelaide) Garreau de Dombasle is an exceptional character, but also a typical illustration of these women’s struggles to take part in European expeditions in the Pacific, and how they successfully participated in the development of sciences (in this case, anthropological science).

In 1848, at just 29 years old, Adèle de Dombasle had just divorced and (we think, based on historical sources) entrusted her three young children to her mother, to embark aboard an expedition ship that should have driven her around the world. She was to be the official illustrator for ethnologist Edmond Ginoux de La Coche on a mission for the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As she set foot on the Marquesas Islands, her intent was to explore the valleys of Nuku Hiva island to draw landscapes and monuments, the inhabitants, their tattoos and their everyday tools. She told the marine officer who tried to discourage her (“as a woman… it’s far beyond her capability!”) that she came “with the unique aim of seeing” the inhabitants, their realisations and their country, to better understand “the intimate characteristics of their existence” (1851, see below).

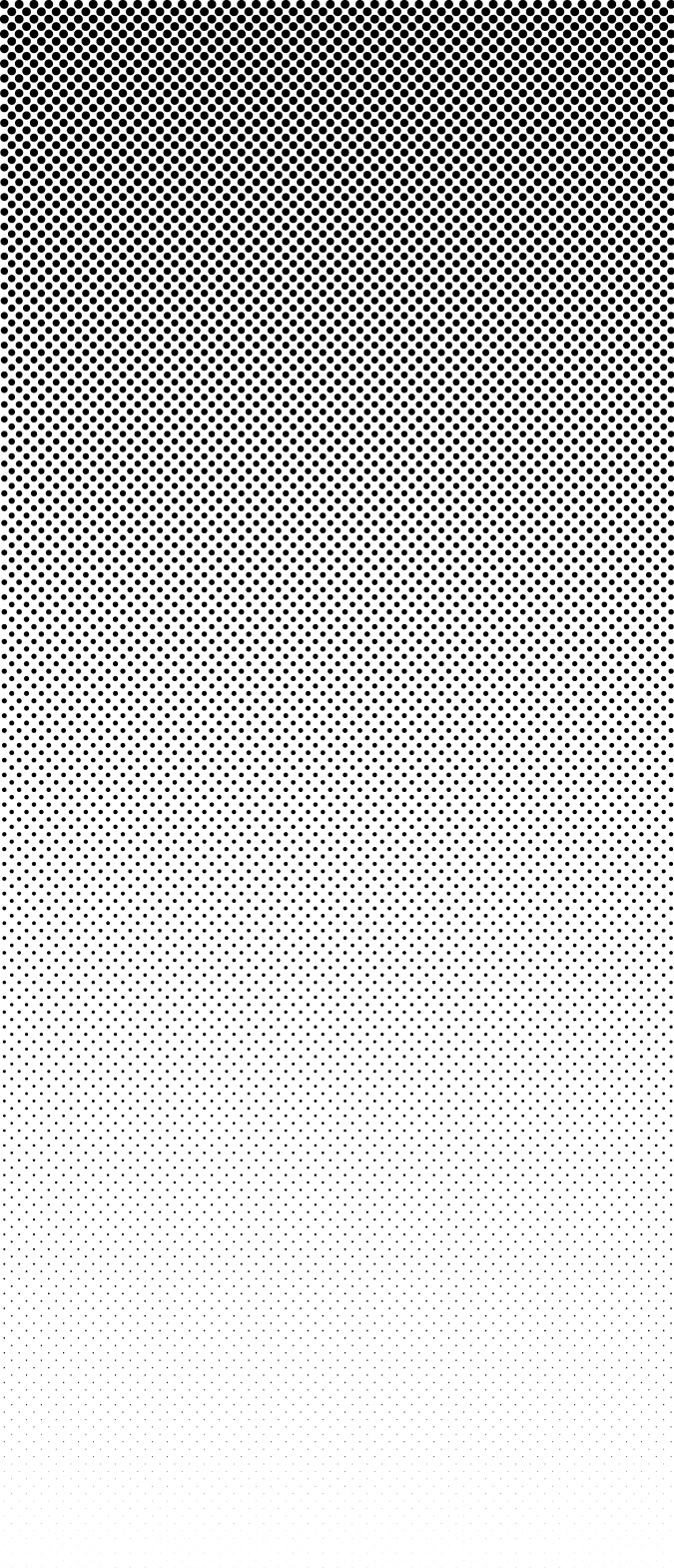

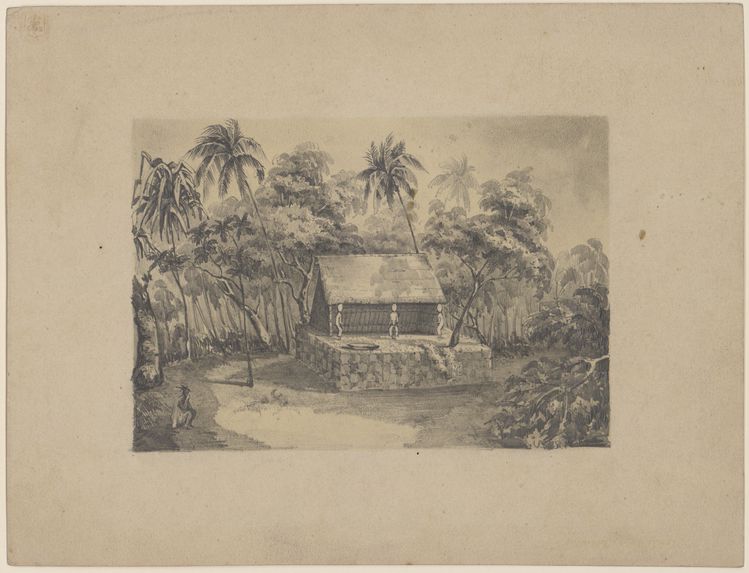

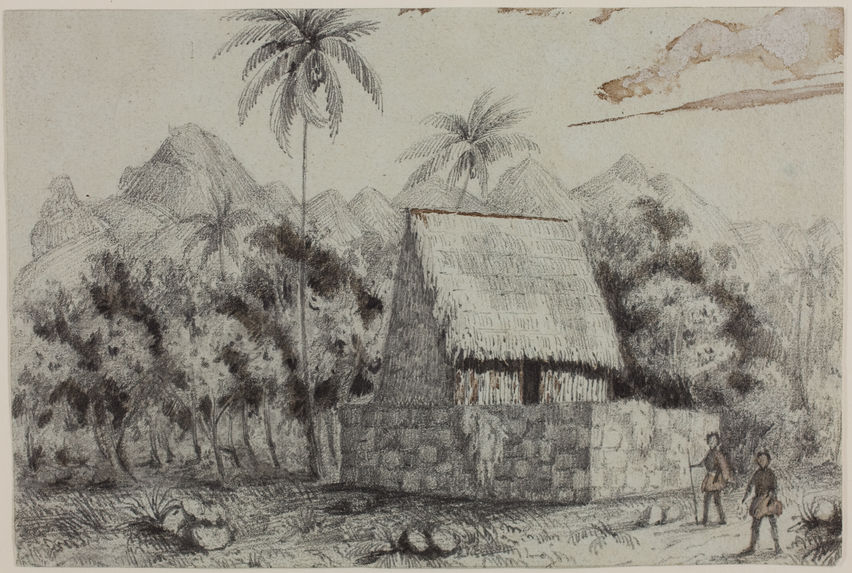

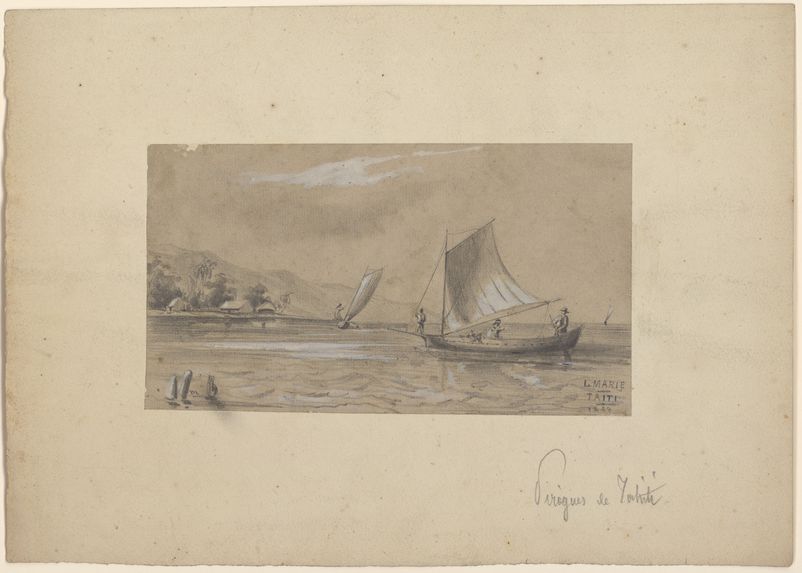

She managed to produce dozens of drawings during her trip to Polynesia (and Chile). These drawings depict various monuments and sites in the Marquesas Islands, the peoples from Tahiti and Marquesas, with some elements of material culture, landscapes and portraits. The details are truly exceptional: plant species are identifiable, tattoos and artefact decorations are finely represented. These drawings are a unique source of information for archaeologists who work in the area today. Unfortunately, only a handful of them are still accessible, including 17 kept at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris.

Adèle was eventually forced to put an early end to her journey, in part because a divorced woman travelling alone with a single male companion was badly perceived by colonial authorities.. However, in 1851, she managed to publish an article that related her experience in Marquesas – outside of academic circles. Her specific position as a woman also allowed her to build connections with the women in Marquesas and Tahiti and to collect artefacts that Ginoux then catalogued – these are kept at Musée de la Castre in Cannes (French Riviera), and she also played a crucial role in maintaining and protecting this collection.

Adèle de Dombasle died at age 82, in 1901. 13 years later, Katherine Routledge would set foot on Rapa Nui and become the first woman ever known to lead archaeological excavations in the Pacific.

Drawings such as the ones Adèle did have been a key element of the French expeditions in the Pacific and Oceania since the 18th century. What do they tell us about the intent of the navigators and the way they perceived the world, and what is their scientific value today?

Of course, these drawings, paintings and engravings played a very important role during the European explorations of the 18th century, then the scientific expeditions of the 19th and early 20th century, especially in the Pacific. They were an essential complement to the written description of the European “discoveries”, and sometimes outlined the discrepancies between the imagination of these early explorers (see for example the European tendency to depict Polynesians with appearances close to Greco-Roman antiquity), and scientific illustrations (see the drawings of Australian fauna and flora by members of French navigator Baudin’s expedition). Such drawings played a role both as scientific documents and as a foundation for European perceptions of the peoples and landscapes of Oceania.

At that time, young women who came from a higher social background were encouraged to learn graphic arts. This very specific skill eventually gave them the opportunity to take part in expeditions and develop their scientific expertise. Adèle de Dombasle is one example, but she’s not the only one. Numerous “wives” of archaeologists or anthropologists did accompany their husbands as assistants to the “official” scientists. This is the case of Willowdean Handy with her illustrations and analyses of various Marquesan tattoo designs in the early 1920s. Worth mentioning is also the lesser known story of countess Régine van den Broek d’Obrenan, who realised various drawings, pastels and even one of the first francophone comics to illustrate the scientific journey she (and four others including her husband) had undertaken to collect ethnographic objects. She was part of the small team involved in the creation of an Oceanist department at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris at the end of the 1930s.

Today, these illustrations represent an incomparable source of information for the historical, archaeological, cultural and anthropological study of Oceanian communities. They are also key historical testimonies that help us better understand how Europeans developed biased anthropological representations of the indigenous populations and environments of the Pacific, which were the primary focus of these expeditions. Finally, as we discover the drawings produced by women, this graphic corpus is a unique opportunity to analyse the impact of gender on representations.

These fascinating stories deserve more publicity – your work deserves more publicity. Where should we go if we want to learn more about it?

There has never been an exhibition specifically dedicated to the women who used their talents as illustrators during scientific expeditions in Oceania.

There have been a few instances where institutions have put a focus on women who became famous as illustrators (see examples here and here or the work carried out by the Australian Museum on the Scott sisters). Some of the drawings by Adèle de Dombasle can be seen at the Musée du Quai Branly, others in a book that Frédéric de La Grandville dedicated to Edmond Ginoux de La Coche (2001. Edmond de Ginoux. Ethnologue en Polynésie Française dans les années 1840. Paris: l’Harmattan)and the musée des explorations du monde (MEM) in Cannes is set to organise an exhibition in 2022 that will present newly acquired drawings thanks to the work of curator Théano Jaillet. A few books exist such as the notebook of Régine van den Broek d’Obrenan, recently published. The ‘Pacific Matildas’ project is presented here and updates are published here, with a bibliographic database and interactive map recently made available online.

The history of these women and their drawings is also rich in lessons learned for our contemporary values and shortfalls – they convey a timeless message about gender equity and inclusiveness.

These drawings are beautiful testimonies of the encounter of alterities, the wonder and curiosity one can experience through travel and, simply, discovery.

But I also think that these drawings, those by Adèle as those that other explorer-illustrator-scientist females realised, are very concrete evidence that minority groups – that is to say groups that will be put in a dominated position by social, cultural and political norms – will always find a way to elevate themselves above their social condition. At the same time, the intersectionality of various factors of oppression – typically class, gender and colonial relationships – will make this outcome a lot harder to achieve.

That’s why it is so important to continue fighting any discriminations today and supporting diversity, including in scientific research. One of the best tools we have is to loudly discuss the figures, such as these women, who played an instrumental role in building our scientific knowledge of the world, but are still hidden behind the “founding fathers” (the infamous “Matthew / Matilda effect”, well identified in sciences). We need to tell the stories of the Matildas of the Pacific.