Review of Two of Us (Deux)

Film critique by Emmanuelle Dunn Lewis

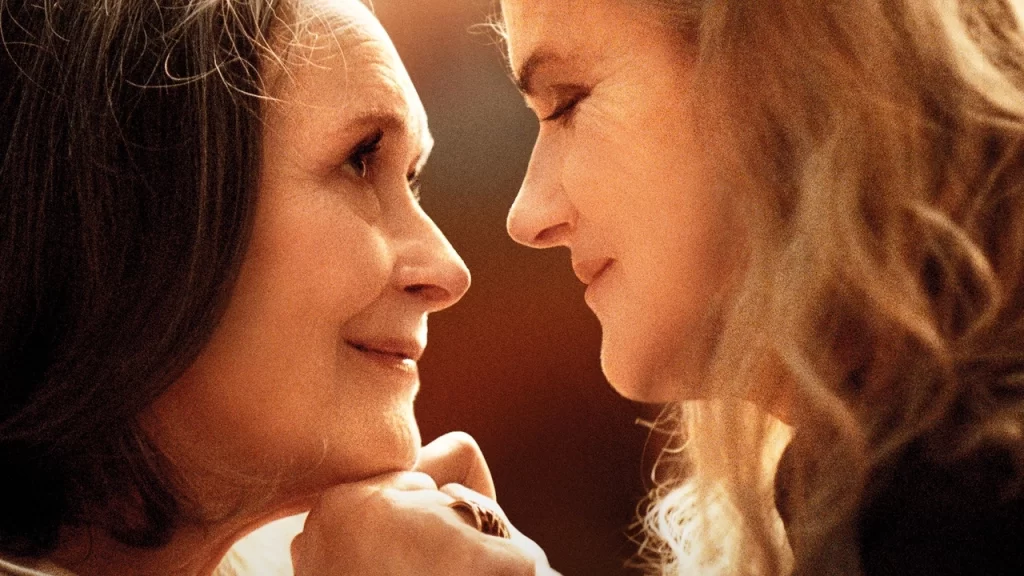

Two of Us (Deux) by Italian director Filippo Meneghetti is a touching reminder of the need to make every moment count. The film’s exploration of the love story of the lesbian couple, retirees Nina (played by Barbara Sukowa) and Madeleine (played by Martine Chevallier), is one that is rarely shown in popular media with romances, and particularly queer romances, which predominantly focus on a younger demographic. Meneghetti thoughtfully reminds us that their story is both unseen and unheard through shots of the couple cloaked in darkness and the relative silence of the soundtrack.

The concealment of their story seeps into the plot itself with Nina and Madeline carefully hiding their romantic relationship from their friends and family under the guise of them being close neighbours living opposite each other. The audience is left agonising over what could have happened had Madeleine introduced Nina to her family as Madeleine’s stroke leaves her without the ability to speak and leads to the lovers being separated.

From the relatively sparse soundtrack alone, we might be fooled into thinking that we are watching a horror film, anticipating a jump scare right around the corner. The silence is unnerving. In the opening scene, a young girl screams in the wind when she cannot find her friend in a game of hide-and-seek, but we cannot hear what she says above the screeches of crows. Like a horror film, we view the protagonists from behind doorways and through windows, giving us the uncomfortable impression that they are being watched. Meneghetti cleverly positions the audience to feel anxious just like Madeleine about the uncovering of her relationship.

Like her, we are also left with silence which teaches us to notice everyday sounds — the smack of lipstick on lips, the crinkle of a bow being untied, the creak of chairs, the jingle of keys in a lock, the rustle of leaves in the wind, the crows of ravens. Being privy to Nina and Madeleine’s secret relationship, the silence declutters our viewing, allowing us to notice the subtle expressions of intimacy between the pair, from dancing barefoot to the smile that they greet each other with across the hallway. Close-up shots of the two of them basked in golden light give us the impression that they are entirely alone with one another, even on a crowded dancefloor or bustling French boulevard.

Yet, time is ticking literally and metaphorically in this film, and the reoccurring chime of the clock on the mantlepiece does not let the audience forget. Like the magic in Cinderella which vanishes at midnight, the film reminds us that our time with others is limited. In many ways, Nina and Madeleine’s love is a naive, hopeless love, or “fleur bleue”. The time they spend together lacks the urgency that comes from knowing they do not have forever. Realising that their days are numbered following Madeleine’s stroke leads Nina to make every effort to spend time with Madeleine. Yet, the extremes she goes to such as throwing bricks and smashing cars paint her as hysterical and do not quite ring true with her characterisation as assertive but measured.

The film shows us that the idyllic entanglement of lovers apart from the rest of the world suggested by the title is deceptive. Their relationship is complexly intertwined with the lives of Madeleine’s children, Frédéric and Anne, who believe that their mother’s one true love was their now-deceased father. The film cleverly draws parallels between the caring and — at times — condescending attitude of parents towards their children and adult children towards their elderly parents. Rather than a teen sitting their parents down to “come out”, it is Madeleine who gathers her adult children and grandson around the table. We see that her children are not necessarily intolerant of their mother’s sexuality, but that they are reluctant to accept that their mother’s true love was not their father and revise their idolised childhood memories. Anne refuses to open the door to Nina both literally and metaphorically as she is unwilling to revise her memory of the past.

The thoughtful exploration of complex relationships, beautiful cinematography and stellar acting make it unsurprising that the film received its fair share of accolades. Meneghetti won the César for the Best First Film, Sukowa and Chevallier shared the Best Actress Award and the film was France’s submission for the Best International Feature at the 93rd Academy Awards. Two of Us is a poignant reminder that love never gets old and to cherish loved ones which is why it is definitely worth a watch.

Emmanuelle Dunn Lewis is a student of French at the Australian National University.