All You Need to Know About El Niño

Oceans are warming rapidly and steadily as a result of climate change, yet, in 2016 this warming was amplified by a particularly strong event called “El Niño”, which pushed the planet into one of the hottest twelve-month periods on record. These powerful events occur naturally and have always existed, but climate change could alter their strength and ferocity in the future.

What is El Niño?

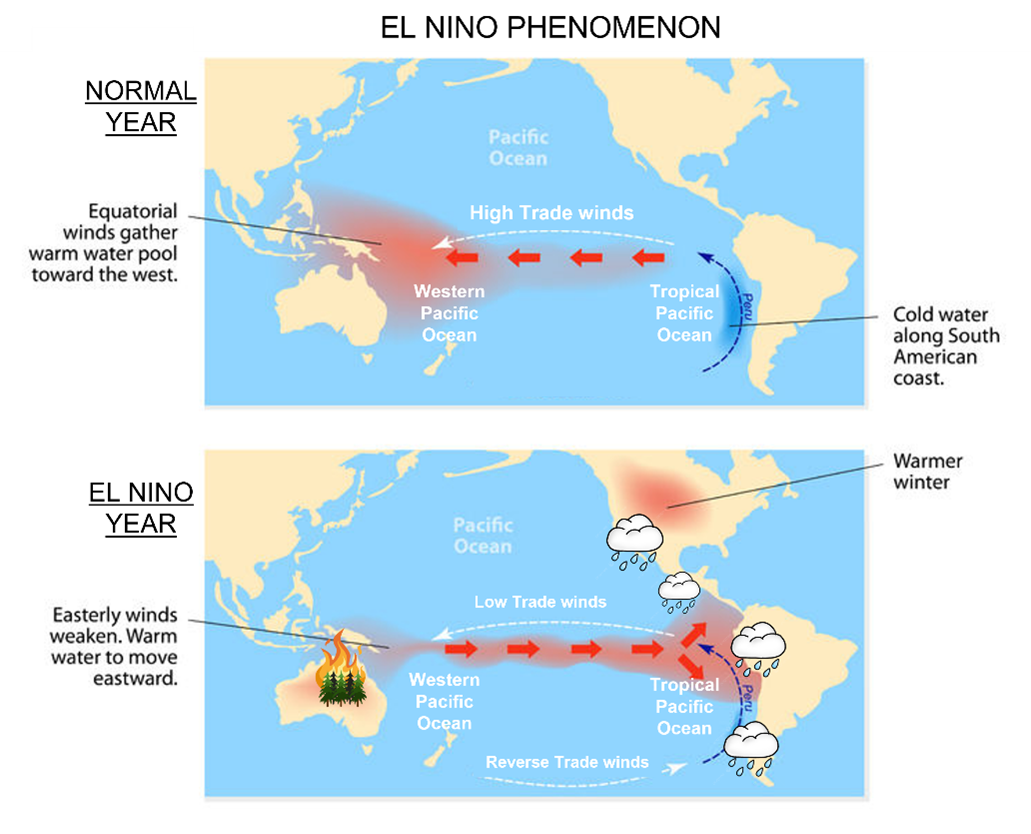

El Niño events are in fact just one half (the warm and wet half) of a natural weather cycle called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). During an El Niño event, the surface of the tropical Pacific Ocean warms more than usual, particularly at the equator and along the coasts of South and Central America. The warming of the oceans leads to the formation of low-pressure systems in the atmosphere, resulting in heavy rainfall along the western coasts of the Americas.

These events can last up to a year, but the warming tends to be strongest during the spring and summer months in the southern hemisphere, i.e., from October to February. In fact, this timing is the source of the phenomenon’s name: in Spanish, El Niño means ‘the little boy’, and the full name was originally “El Niño de Navidad”, meaning the Christmas child. In the 1800s, Peruvian sailors chose this name to describe the invasion of warm water that occurs every year around Christmas along the coasts of Ecuador and Peru. Today, the name has stuck to describe the accentuated warming of surface waters near the coasts of South America.

Why does El Niño happen?

Camille Risi, a climate expert from CNRS, France, explained: “This is a natural phenomenon caused by winds from the Pacific Ocean known as the Trade Winds. Under normal circumstances, these tropical winds blow from east to west in the Pacific, pushing the water westwards towards Indonesia and Australia. The ocean surface accumulates heat in the western Pacific and cold water in the east.

Every two to seven years in general, these winds weaken or reverse: this is what we call “El Niño”, Camille Risi sums up. This generally lasts between nine and twelve months. The meteorological phenomena are therefore reversed, with warmer water accumulating to the east of the Pacific and colder water to the west. In tropical areas, rainfall occurs when the water is warm. In fact, “the cumulonimbus clouds responsible for thunderstorms form when the warm air rises”, explains the researcher.

The periods when the El Niño phenomenon occurs are synonymous with major meteorological upheavals, and even disasters. The Western Pacific, i.e., Australia, deprived of rain, is affected by severe drought, sometimes leading to bushfires. Conversely, the Eastern Pacific, i.e., Central and South America, experiences unusually heavy rainfall, flooding and landslides.

More generally, all areas of the world are affected, in one way or another, by El Niño. Abnormal rainfall occurs and global temperatures rise. The African continent often feels the consequences: the South dries out while the Horn of Africa becomes wetter. “In general, the years affected by the phenomenon turn out to be among the hottest on a global scale,” concludes Camille Risi.

The effects are even greater in the second year of the phenomenon, according to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). The current El Niño episode began in June 2023 and continues into 2024. WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo states that “since June 2023, every month has broken the monthly temperature record, and 2023 is by far the warmest year on record”.

Scientists still don’t know exactly what triggers the cycle. But they can spot the signs of a nascent El Niño very early on, and they have a good idea of how the events develop once they are triggered.

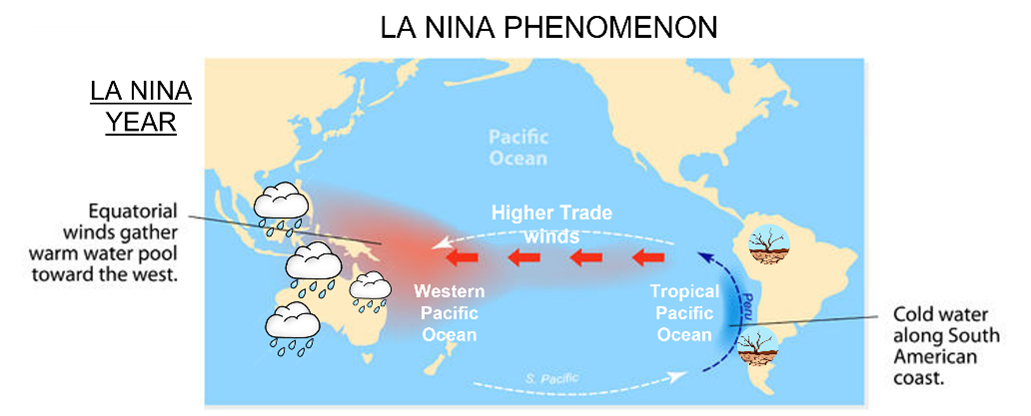

What about La Niña?

The other half of the ENSO phenomenon is generally referred to as “La Niña”. It is basically the opposite: ocean temperatures along the eastern half of the tropical Pacific cool and this part of the world dries out. The band of warmth and rainfall shifts to the other side of the ocean, meaning that Australia, Indonesia and South-East Asia become wetter and warmer than usual. La Niña events tend to last longer than El Niño events, persisting for between nine months and two years. In between a full ENSO phenomenon, ocean temperatures and rainfall patterns normalise.

The other half of the ENSO phenomenon is generally referred to as “La Niña”. It is basically the opposite: ocean temperatures along the eastern half of the tropical Pacific cool and this part of the world dries out. The band of warmth and rainfall shifts to the other side of the ocean, meaning that Australia, Indonesia and South-East Asia become wetter and warmer than usual. La Niña events tend to last longer than El Niño events, persisting for between nine months and two years. In between a full ENSO phenomenon, ocean temperatures and rainfall patterns normalise.

Is the ENSO phenomenon getting stronger with climate change?

Since El Niño has always existed, climate change is not responsible. On the other hand, researchers believe that the two events are adding up, aggravating the rise in temperatures and natural disasters. As a result, according to the European observatory Copernicus, the temperature of surface waters broke its monthly record in February 2024, with an average of 21.06°C.

Over the current period, Celeste Saulo believes that “El Niño has contributed to these record temperatures, but greenhouse gases, which trap heat, are unequivocally the main culprits”. She adds that the high-water surface temperatures in 2024 are “worrying, and cannot be explained by El Niño alone”.

Finally, Camille Risi adds that according to the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the direct link between this event and climate change is not clear. “Still, the consequences of El Niño oscillations on changes in rainfall and its extremes will increase with climate change”, she concludes.

This article is taken from the ‘l’info durable’and national geographic websites.