Interview with the NGV curators behind the Pierre Bonnard exhibition

Ted Gott and Miranda Wallace

- What inspired you to curate an exhibition of Pierre Bonnard’s work, and what makes his work so unique and noteworthy?

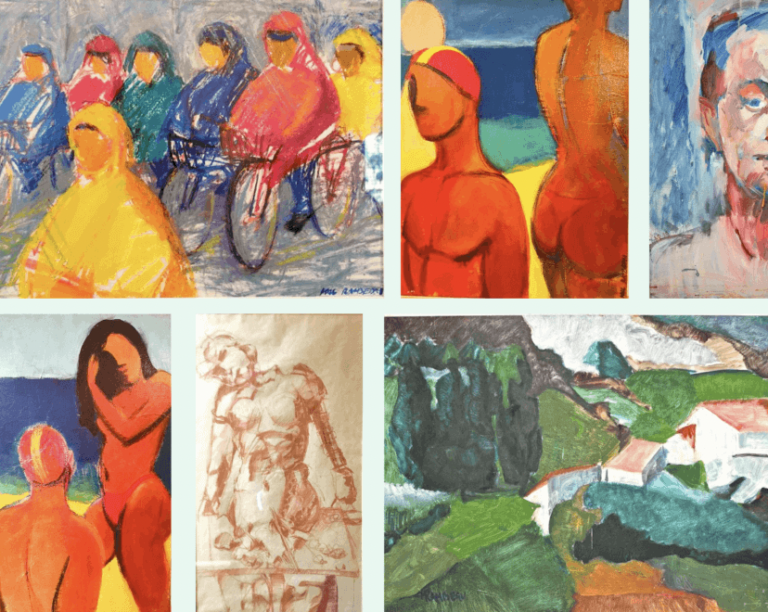

We have been delighted to work with the Musée d’Orsay, and with Isabelle Cahn, emeritus Senior Curator of Paintings at the Musée d’Orsay, to create the largest and most comprehensive survey of Pierre Bonnard’s work ever to be staged in Australia. We wanted to bring late 19th and early 20th century France to life through displaying paintings, drawings, prints, photographs and decorative objects by Pierre Bonnard. What makes his art so unique is the way in which he worked in so many media, and embraced modernity in all its emerging forms, from the birth of cinema, to the use of photography as a creative tool, and the adoption of the motor car to take him throughout the French countryside in search of motifs to draw and paint. His multi-faceted work will be shown in this exhibition alongside early cinema by the Lumière brothers, and artworks by Maurice Denis, Félix Vallotton and Édouard Vuillard, Bonnard’s early contemporaries.

- What challenges did you face in curating this exhibition, and how did you go about selecting the pieces that will be on display?

It is always a challenge negotiating international loans for large exhibition projects such as this one. The exhibition features loans from the Musée d’Orsay, which holds the world’s largest collection of Bonnard’s work, along with significant loans from other museums and private collections in France as well as elsewhere in Europe, the UK, the USA and Australia. International lenders include Tate, London; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; Minneapolis Institute of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Art Institute of Chicago. We wanted to present a show that would capture every aspect of Bonnard’s incredible life and career; and so we had to consider which works to borrow, and from where, to create a truly immersive exhibition experience for the visitor.

Tracing the Pierre Bonnard’s emerging artistic practice in the 1890s, the exhibition starts with the artist’s paintings and prints recording Parisian street life, which contain rich and often satirical observations of what Bonnard called the ‘theatre of the everyday’. The exhibition then follows the artist’s career in the first decades of the 20th century, when his perspective shifted to a more domestic vision of the life he shared with his life-companion, Marthe Bonnard. The landscape became a primary subject for Bonnard from around 1910 onwards, influenced by his friendship with the painter Claude Monet, a near neighbour in the Normandy countryside until Monet’s death in 1926. For Bonnard, landscape painting was a hybrid genre and often included glimpses of interiors and still lifes. Bonnard’s life shifted largely to the south of France from the 1920s onwards, leading to the preponderance of highly coloured, iridescent landscapes capturing the light and life of the South. It is these last paintings for which Bonnard is most celebrated and the exhibition features iconic examples from international collections in France and the United States.

One of the biggest challenges that this exhibition faced was that it was originally scheduled for mid-2020 but was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been realised now due to the swift and generous agreement of many lenders – particularly our major partner the Musée d’Orsay – to recommit their loans for 2023.

- In the exhibition, you showcase a new installation by acclaimed designer India Mahdavi. How do you think Mahdavi’s work enhances the experience of viewing Bonnard’s paintings, and what do you hope visitors will take away from this unique collaboration between a designer and an artist from a different era?

India Mahdavi (b. 1962) is a French architect and designer widely celebrated for her use of colour, form and texture. Combining these foundational elements of design, she has created immersive environments in restaurants, hotels, retail interiors, art galleries and public spaces around the globe. She is truly one of the design icons of our time. Her shared passion for utilising colour, texture and form to elicit certain memories and emotions, paired with her deep appreciation of Bonnard’s practice, made her a natural and authentic choice to create the scenography for this exhibition. Bonnard’s works possess both a sense of pensive contemplation – a wistful longing, perhaps – and joy in the colour and mercurial nature of paint. His paintings radiate within the spaces they inhabit, filling rooms with ‘shimmering colour’, to quote Antoine Terrasse, Bonnard’s great-nephew. They also provoke a range of sensations in their viewers, from pure pleasure in the visual to a curious and pensive sentimentality in response to the scenes of domestic life. We hope that visitors will understand and enjoy Mahdavi’s attraction to Bonnard as an artist whose work evinces contrasting moods and feelings, and who creates complex worlds with colour and light, which reveals something of her own approach to interior design. Mahdavi describes our relationship with the spaces where we ‘live, work, learn, share, eat, play, love and dream’ as ‘both physical and emotional’.

- What was the process of incorporating Mahdavi’s design elements into the exhibition? Can you talk about any particularly interesting or challenging aspects of this collaboration?

For this exhibition, Mahdavi has encountered Bonnard’s work anew, seeking to create, in her own words, ‘an impression of his world, through my own eyes’. In a scenography that expresses the deep affinity between artist and designer, Mahdavi has shaped the galleries into interiors for Bonnard’s art, with furniture, lighting and wallpapers based on elements of her favourite paintings by Bonnard. India Mahdavi visited Melbourne in 2019, to gain a sense of the National Gallery of Victoria’s exhibition spaces. This was essential for her to be able to marry her vision of a Bonnard-inspired design with the installation of the Bonnard project here at the NGV. Located in the rue Las Cases in Paris’s 7th arrondissement, India’s studio is a mere 400 metres from the Musée d’Orsay, which houses one of the largest collections of Post-impressionist masterpieces and, fortuitously, the largest single collection of Pierre Bonnard’s paintings in any museum in the world. Designing interiors allows Mahdavi to create new worlds, inspired both by the characteristics of the site or setting at hand and also by unconscious memories of colours, textures and shapes. Affinities in their approach to colour and texture, as well as a shared interest in the domestic realm, make this exhibition the perfect opportunity for Mahdavi to meet Bonnard in the twenty-first-century museum.

- What do you hope visitors will take away from the exhibition, and what impact do you think it will have on the wider art community?

Pierre Bonnard is not yet a household name in Australia. It is our fervent belief that this spectacular exhibition is going to change that, making Bonnard a permanent presence in the collective consciousness of Australian art lovers. A member of the artistic movement the Nabis, Bonnard, along with his fellow artists, worked across a wide range of media, embracing painting, book illustration, posters, ceramics and theatre decor. This is what we think will excite the wider art community, many of whom already work across a similar range of media in their daily practice. We also hope that all visitors to the exhibition will spend time with Bonnard’s later paintings, which are incredibly complex in their structure and multiple narratives. These are works that really reward ‘slow looking’, in a world where we are bombarded with instantaneous visual materials from all sides in age of the internet, mobile phones and electronic advertising in our streets.

- How do you think Bonnard’s work has influenced contemporary art, and what relevance does it have to today’s society?

Pierre Bonnard is one of the most beloved painters of the twentieth century, celebrated for his ability to use colour to convey deep emotion. Bonnard was declared by his close friend Henri Matisse as ‘a great painter, for today and definitely also for the future’. Bonnard as a painter has had an enormous impact on the development of contemporary art, his works having been revered by artists for decades since his death in 1947. As a young man, when he was part of the group of artists who called themselves the Nabis (the prophets), Bonnard sought to be ground-breaking and transformative in his approach to art. The Nabi artists considered themselves the prophets of a new design-based art that would encompass every sphere of modern life – interior design, furniture, fans and textiles, stained glass, and commercial illustration and advertising. The Nabis were also committed to treating the surfaces of their paintings as a site for exploration of flat colour and linear design above all, before narrative concerns. This emphasis on the primacy of design, design for living even, makes Bonnard extraordinarily relevant for contemporary art’s current intersection with the worlds of architecture and design.

- As an exhibition curator, what role do you think cultural exchanges, such as the showcasing of a French artist’s work in an Australian museum, play in fostering positive relationships between countries and promoting cross-cultural understanding?

As curators, we are always thrilled when we are able to bring highlights of another society’s culture to Australia. Cultural relations between Australia and France have been strong ever since Napoléon sent Nicolas Baudin to explore Victoria in 1800 (when he named our state Terre Napoléon), and he brought Australian flora and fauna back to Joséphine at Malmaison. In 1889 Melbourne’s opera singer Nellie Melba was the toast of Paris, settling into a new apartment on the Champs Élysées; while in 1891 the most famous actress in the world, Sarah Bernhardt, wowed audiences at Melbourne’s Princess Theatre with her performance in La Dame aux camélias. Within months of the Lumère brothers unveiling their new film invention, the Cinématographe Lumière in Paris, their crews were operating in Australia, famously recording the Melbourne Cup in November 1896. The influence of French food and viniculture in Australia has been profound; and, our two countries have been united together in defence of France in both the world wars of the twentieth century. Cultural exchanges like the NGV’s Bonnard exhibition serve to remind us of the close bonds that connect our two countries, promoting continued understanding of the many ties that bind us together.

- Can you talk about any particularly interesting or surprising aspects of Bonnard’s life or artistic career that visitors might not be aware of?

There are many surprises for visitors in this exhibition. One of these is the presence of films by the brothers Auguste et Louis Lumière, who pioneered cinema in France. Bonnard was introduced to them by his brother-in-law Claude Terrasse, and their early films influenced Bonnard’s art in the late 1890s. Another surprise will be Bonnard’s involvement with both music and experimental theatre at this time. In 1890 Bonnard’s sister Andrée had married Claude Terrasse, a composer and music teacher, and Bonnard subsequently collaborated with his brother-in-law on illustrating the latter’s musical primer for children, as well as Terrasse’s musical scores. In 1891 Bonnard moved into a studio at 28 rue Pigalle in the ninth arrondissement, which he shared with Maurice Denis, Vuillard and the young actor Aurélien Lugné-Poe. Through Lugné-Poe’s connections, he now became involved in the contemporary experimental theatre scene in Paris. Lugné-Poe’s friend Paul Fort founded the Théâtre d’Art in 1890, which he conceived in opposition to the prevailing taste for naturalistic representation in French theatre. Bonnard was to design stage sets and playbills for Fort’s Théâtre d’Art productions; and, later, worked for Lugné-Poe’s own theatrical company, the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre. In 1896 he worked with Terrasse and Lugné-Poe on the staging of Alfred Jarry’s controversial play Ubu Roi (King Ubu). Bonnard also worked on the Théâtre des Pantins (Puppet Theatre) that he, Terrasse, Jarry, and the poet Franc-Nohain established in 1897 in the garden of Terrasse’s residence near Montmartre. Bonnard made some 300 puppets for the Pantins productions, as well as illustrating the sheet music for songs by Franc-Nohain that were scored by Terrasse. So, Bonnard, cinema and puppets, who knew?

- What is your favourite piece in the exhibition, and why?

This is always a difficult question to answer, as one’s favourite work can change daily sometimes! But a true favourite remains Bonnard’s great painting, first exhibited at the Salon de la Société des artistes indépendants in Paris in 1892, Twilight, or The croquet game (Crépuscule, ou La Partie de croquet) 1892, which is being loaned by the Musée d’Orsay. This is a spectacular depiction of summertime play at the Bonnard family estate at Grand-Lemps, near Grenoble, where Bonnard’s sister Andrée and brother-in-law Claude Terrasse are shown playing croquet with another couple, while young women dance on the grass in the background. Reflecting the Nabis’ commitment to treating the surface of a painting as a site for exploration of flat colour and linear design, Bonnard here intermingles the dense patterns of fabrics and foliage into a single surface of interlocked silhouettes. This work is enormous in scale, and is a highlight of the exhibition’s opening gallery.

- Can you discuss any upcoming projects or exhibitions at the National Gallery Victoria that may also feature any art pieces from France or the francophone area ?

The NGV has had some amazing new acquisitions that will be of great interest to francophones everywhere.

Sandra Bardas OAM and David Bardas AC recently donated a magnificent cast of Auguste Rodin’s Walking man (L’Homme qui marche, moyen modèle) (conceived 1899–1900, cast 1964). Working at the same time as Impressionist painters who were changing perceptions of art, Rodin challenged the conventional notions of sculpture. One of his most significant contributions was to present the incomplete human form; naked figures often headless, missing limbs and lacking the usual refinement. This concept of legitimising non finito works redefined artistic practice in Europe. Rodin’s most recognised and admired work in this reductionist mode is his Walking man, that he adapted from his earlier sculpture John the Baptist.

Through the generosity of Krystyna Campbell-Pretty AM and Family, the gallery has received the gift of five new French paintings, of extraordinary quality and interest.

Marie Victoire Lemoine’s A young woman leaning on the edge of a window (Une jeune femme appuyée sur une croisée) 1799 is a life-size portrait by one of the most prominent women artists working during the French revolutionary and Directorate periods. The painting shows a young woman standing before a windowsill, upon which is propped a largish book; she toys with its pages with the fingers of her left hand, gazing languidly out at the viewer. When exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1799, this portrait could not have looked more up to date, given the new fashion under the Directoire for all things à la Grecque.

Two new paintings by Louis Léopold Boilly also expand our holdings of French paintings from this period. An artist whose career spanned many genres and also extraordinary political and social times, Louis Léopold Boilly lived and worked through the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution, the Directorate, the Napoleonic Empire, the restoration and the July Monarchy. His The lacemaker (La Dentellière) c. 1789-93 is a fine example of the small genre pictures that Boilly produced in these years, in which he updated the seventeenth-century Dutch genre picture for a late-eighteenth-century French audience. His The two sisters (Les Deux Soeurs) c. 1800 is one of Boilly’s depictions of everyday life, known as genre painting, that focused in particular on representing family. In this painting, the delicate and almost porcelain-like touch of Boilly’s hand as a painter emphasises the tenderness of the protective gesture of an older sister towards her younger sibling.

Louise Abbéma’s Portrait of Renée Delmas de Pont-Jest 1875 is a ravishing painting by this accomplished French painter, sculptor, and designer of the Belle Époque. The sitter here is Marie-Louise-Renée née Delmas de Pont-Jest (1858–1902), an actress and sculptor, who was also one of Abbéma’s closest friends. Seated at a desk, she holds a letter written on a sheet of black-bordered mourning stationary, and seems to be penning a condolence note in response. The sitter was later to marry the acclaimed actor Lucien Guitry, and was the mother of the film director Sasha Guitry.

Finally, the NGv’s twentieth century collections have been immensely augmented by Suzanne Valadon’s Nude with drapery (Nu à la draperie) 1921. Suzanne Valadon was a completely self-trained artist. She had worked, however as a model from the age of fifteen in the vibrant art world of Paris in the late nineteenth century. Artists who she posed for included Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Jean-Jacques Henner, Théophile Steinlen, and avant-garde painters Berthe Morisot, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir among others. She became very close to Edgar Degas and they remained life-long friends. Possessing natural talent and a wonderful eye, she learnt much from observing the artists for whom she modelled. She painted still lifes and landscapes, but her specialty was painting the naked female form.

Ted Gott, Senior Curator of International Art, National Gallery of Victoria

Miranda Wallace, Senior Curator, International Exhibition Projects, National Gallery of Victoria